Like so many teachers and parents, it was the dances that I noticed first.

Compared to the fistfights I broke up over Instagram comments, or the cry of adolescent rage, “you’re breaking my [Snapchat] streaks”, in 2019 TikTok appeared to be the most benign of the new apps. At least they’re doing something creative, I thought. The dances seemed innocent and even collaborative, something to encourage if they weren’t taking place during my English class.

Despite being popular, in 2019 TikTok had a certain ‘cringe factor’ to it. “They’re filming a TikTok again”, boys would roll their eyes and gesture dismissively at a huddle of girls. Most of the boys in my class identified as ‘gamers’, focusing late nights on Fortnite, GTA or Clash of Clans and sneering at ‘the dancing app’.

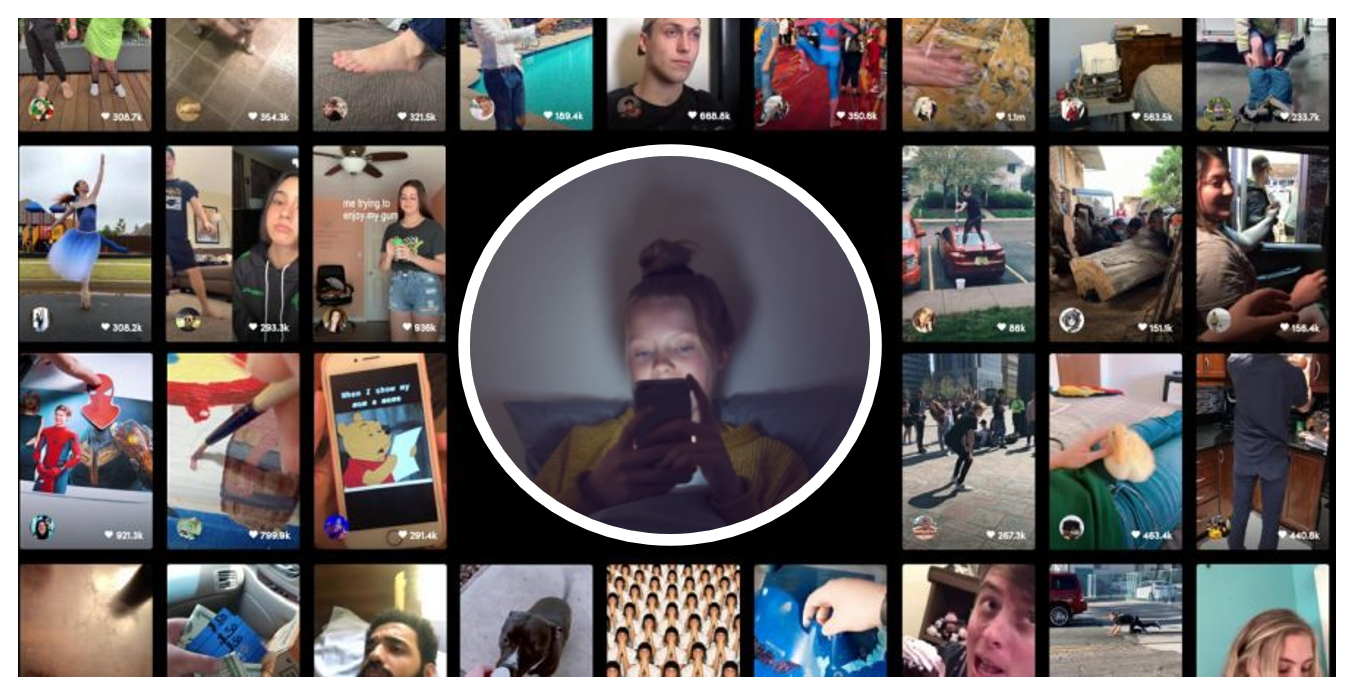

Then during the early days of the pandemic, I noticed a shift. Suddenly all 8th graders had the app. The dances became less common in favour of what we in the staffroom called ‘TikTok zombies’ – students slouched over watching an endless stream of video-content with their heads buried in a hoodie or behind a bag. Unlike the intense Snapchat phone seizures, students were almost disorientated when we asked for their devices, looking up like they’d just woken from a deep sleep.

It was around this time I downloaded TikTok myself. Initially I did it to develop some lessons around the app’s algorithm, which I had heard was uniquely powerful and personal. I created the lessons but kept the app. There were just too many funny clips or discoveries I seemed to make. I watched fellow teachers vent about pandemic teaching and short clips from my favourite comedians.

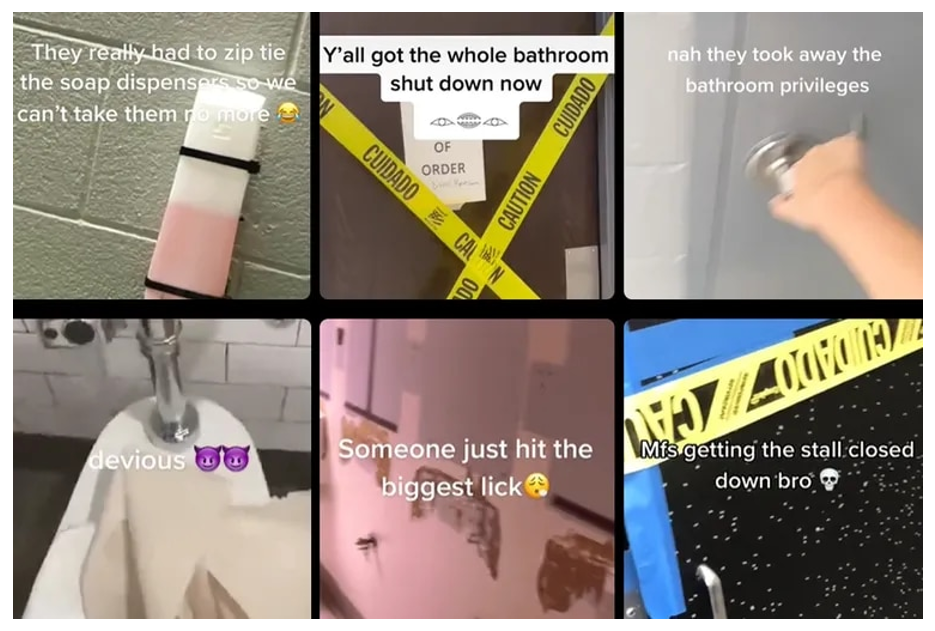

I liked that TikTok clued me into the trends that swept through school. I knew to ask if mothers or grandmothers would like to hear the full lyrics when students chanted “now from the top, make it drop” and then exploded into giggles. I had a hunch about the motivation behind vandalism of the school’s bathroom and where the incriminating video could be found.

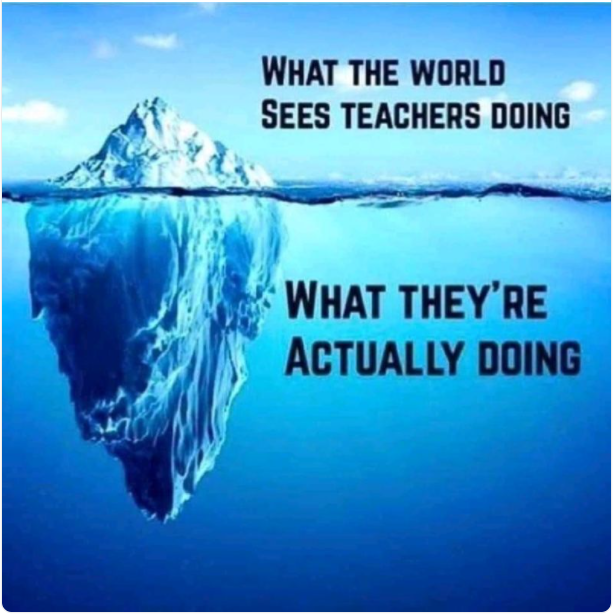

Best of all, I didn’t have to do anything to find this content. The clips just appeared. If a clip didn’t connect within a few seconds, with no conscious thought I flicked to the next. Compared to my engagement with YouTube or Instagram, using TikTok felt like switching from drinking from a slow dripping tap to drinking from a firehose.

Yet while my up-to-the-minute pop culture references improved, I noticed I was also becoming more distracted. A lifelong reader (and English teacher), I found it more difficult to wind down with a novel. More and more, I would look down at my phone, look up, and realise twenty minutes had passed. Coming out of this TikTok flow, I could relate to the TikTok zombies at school. I did the math and calculated that that in twenty minutes I might have scrolled through well over 100 clips.

My experience with TikTok is not a design flaw but a feature. TikTok’s goal is to maximise ‘time on app’ and following the social media business model, it is users who generate the content. TikTok’s ‘special sauce’ is its ability to curate an endless stream for each individual viewer. To do this, the app tracks every millisecond a user engages with each clip. This includes whether you like or share, follow the creator, pause, replay or skip. With an average clip length of between 20 and 30 seconds, TikTok is able to harvest hundreds of micro-signals even in a ten minute session.

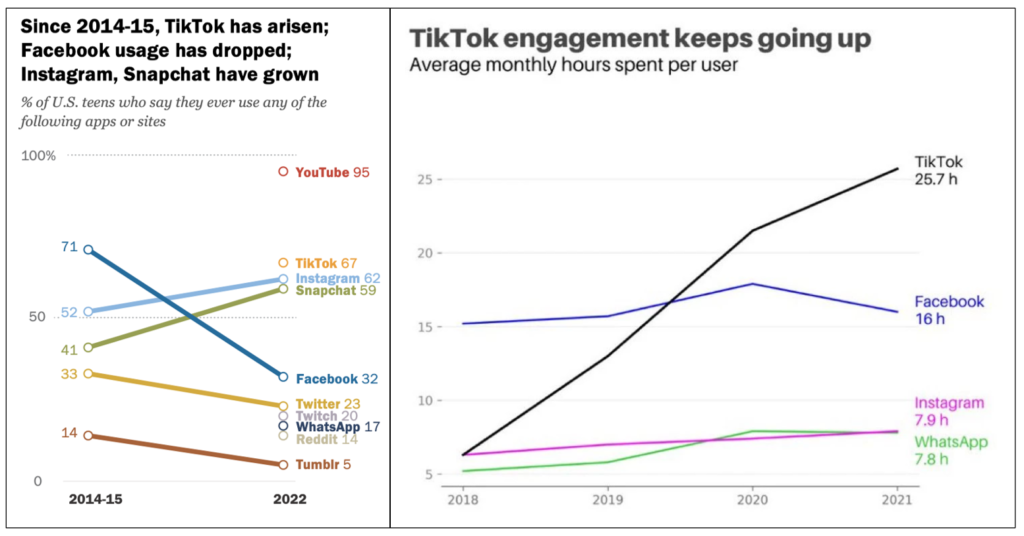

The young TikTokers I see today are dancing less and watching more. The latest research shows US teens now spend more time watching TikTok than YouTube, spending an average of 99 minutes per day on the app. Another 2022 study from Pew Research found 16% of US teens use TikTok “almost constantly” and a third (36%) admitted they “spent too much time” on the app.

I was lucky enough to grow up in the social media ‘before times’. While MySpace made a dent in my later teenage years, I was starting university before Facebook was a feature. As someone who works with young people, I am shocked at how different growing up a digital native is. Social media has made teen life more public and fraught, but these days I wonder most about the effects of TikTok.

Emerging research is worrying. A 2021 study using fMRI showed TikTok’s recommended videos activate the reward centres in the brain at a significantly greater rate than general interest videos. This year, a lead researcher in an ongoing National Institute of Health study shared early results indicating, “when brains repeatedly process rapid, rewarding content, their ability to process less-rapid, less-rewarding things may change or be harmed”.

A generation of young people conditioned to expect instant gratification does not sit well with our existing education system, or with how the brain develops. The prefrontal cortex – the area of the brain responsible for decision making and impulse control – isn’t fully developed until the age of 25. The majority of TikTok’s audience are aged 10 – 19.

While we do not yet definitively know what the effects of short-form media are on developing minds, it would be surprising if TikTok in its current form proved to enhance concentration, self-control, and self-regulation. This certainly wasn’t my initial experience.

Yet despite my concerns, I still use TikTok. Now I am much more conscious of the time I spend on it. For me, understanding how the algorithm works robs it of (some of) its power. I laugh to myself when I find my TikTok feed flooded with something I replayed or lingered on in a previous session. As a teacher, I wish there was a dedicated time to share this kind of information with my students.

Meaningful digital literacy offers an alternative path to China’s model of simply time-restricting the app and legislating the kind of content allowed to go viral. If we can really explore how TikTok works in classrooms, perhaps we can avoid some of the damage already wrought by other platforms?