As another school year begins in Australia, for the first time in seven years I am not eagerly unwrapping a new set of whiteboard markers, arranging desks, or pestering administration for a class list or relief teaching roll.

Instead, I am roughly 15,000 kilometres away in Atlanta, Georgia, and I’m thinking about why I left teaching. Well, ‘left teaching’ is a little dramatic. Even before I departed Australia, I was experimenting with part-time and relief teaching, looking for a balance between running a classroom and running my own business that was both sustainable and productive.

While I do want to return to the classroom at some point, for now there are there are two broad stories I tell about teaching. Both are equally true, yet very different. The first is the positive one. In and around Darwin I taught creative, witty, resilient and fiercely intelligent young people who made me optimistic for the future. I also worked with some amazing educators who I hope will be lifelong friends. The other is the less positive one. I left my vocation feeling exhausted and occasionally defeated by the ever-expanding scope of a job in which I always felt two steps behind where I needed to be to really help my students succeed.

With some distance, I can now see that the second story is largely the result of a gap between the job description and the reality of modern classroom teaching. The bridge across this gap is shadow work. Essential in our current system, excessive shadow work is a destructive force within modern teaching. Tragically, the burden of shadow work is heaviest in low socio-economic, high-trauma settings where progress is needed most. But it doesn’t have to be. If we can bring shadow work into the light, all teachers will be better supported, and our students can truly flourish.

So, what is shadow work? Shadow work is unpaid and unrecognised labor. The phrase dates back to 1981 when Austrian social critic Ivan Illich used it to describe the housework and child-rearing traditionally seen as “a woman’s role”. In recent years the term has had a modest resurgence. In Craig Lambert’s 2015 book, ‘Shadow Work: The Unpaid, Unseen Jobs That Fill Your Day’, Lambert extends ‘shadow work’ to include menial jobs that have been outsourced to consumers like bagging groceries, pumping gas and booking flights.

To understand the shadow work of educators, it is first necessary to review a classroom teacher’s working day. Basically, classroom teachers have ‘contact hours’ which is the time spent in front of a class. In my experience this is around 70% of a school day. The other 30% is where teachers are expected to complete a vast and ever-growing array of tasks. These include attending meetings, planning lessons, marking and providing feedback on student work, collecting and recording behaviour data, following up on wellbeing concerns, contacting parents, supervising and/or organising extra-curricular activities, answering emails and evaluating their own practice.

While some of these tasks are timetabled (like attending meetings), the majority are not. As they spill beyond work hours, they become shadow work. Some of this shadow work is an expected and long-established part of the teaching profession. For example, marking student work and writing reports typically take place after hours but are compensated by the length of the school holidays. The problem arises when shadow work becomes so labour intensive it eats away at teachers’ ability to do their core role well. This impacts not only teachers but also students.

Based on my seven years in the classroom, I am convinced the most time-consuming, complex and consequential shadow work teachers do is lesson planning. This hunch is supported by a just-released 2022 Grattan Institute survey of 5,442 Australian teachers in which 90% of teachers reported they “don’t have enough time to prepare effectively for classroom teaching”. So why is the lesson planning burden on teachers today so heavy?

The fact is, while preparation has always been part of teachers’ work, the requirements for effective lesson planning have changed dramatically in scope, size and significance in recent years. These changes have been supersized by the pandemic. As we constantly hear in the media and see in the financial and job markets, we are in a ‘new reality’. The problem is the vast majority of existing curriculum is not updated for this ‘new reality’. Even the most experienced and skilled teacher cannot magically transform 20th Century style textbook content into engaging 21st Century digital learning experiences.

Instead, many teachers do hundreds of hours of unpaid shadow work attempting to create relevant and engaging lessons that meet the needs of their students. The pandemic has compounded this, forcing teachers to pivot into delivering their lessons online. This in turn has necessitated the digitalization of lessons, which is (unfortunately) not as simple as typing up or scanning existing materials. Often activities created for classrooms full of students simply don’t translate to at-home all-digital classes and need to be reimagined and redesigned. Documents also need to be uploaded, reformatted and functionality added. More shadow work.

The burden of this untimetabled shadow work is damaging to both teachers and students. Teachers who are stressed and overburdened are unable to be at their most effective – whether their students are in-person or online. This stress directly impacts student outcomes. Furthermore, when the vital work of updating and digitalizing lessons is pushed to the margins, the quality of lessons suffers. Again, peer-reviewed research shows that the “students need to be actively engaged in order to achieve… [and] the academic tasks teachers assign are the central aspect influencing student engagement”. So, what can be done?

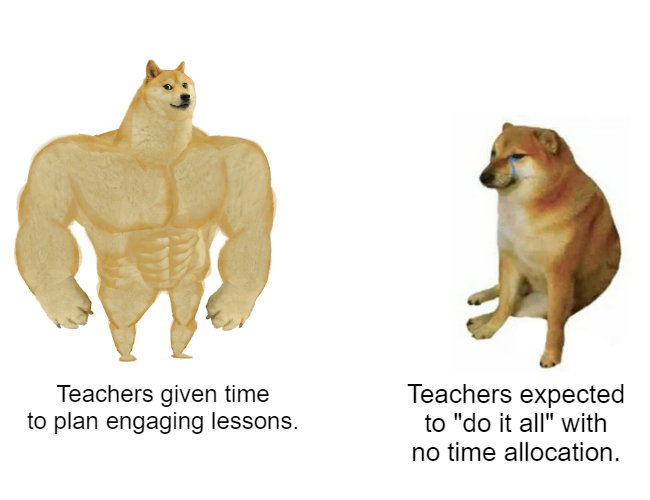

I believe part of the solution is surprisingly simple. Give teachers clearly defined time each week, and a budget, to do the shadow work of lesson and unit planning. Don’t outsource the role to a middle management ‘Curriculum Manager’ or ‘Assistant Principal’. Instead empower individual educators and teams of teachers to create, curate, adapt and share materials that meet the needs of their learners. Teachers need to have allocated time to do their planning. A reasonable allocation would be ninety minutes of allocated planning time per subject per week. As most teachers have four to five hours of contact time per subject per week, this additional time would ensure teachers can have engaging, relevant and rigorous materials ready for every class.

This system would also encourage school administration to prioritize ‘doubling up’ teaching loads, where a teacher might teach two or more courses of the same subject. Especially in middle and high schools, it is an open secret that doubling up teaching loads halves planning. As there is currently no organisational incentive to do this, many schools will allocate teachers four or five different subjects and year levels. This results in an unsustainable planning burden. A much better allocation of resources is to have teachers doubling up on subjects, so one planning session can cover two (or more) subjects. Extra preparation leads to better lessons, better engagement and better results. Teachers who have developed strong programs over many years could use dedicated planning time to make incremental improvements to programs, coach less experienced colleagues and provide their students with more frequent and targeted feedback.

Giving teachers a time-allocation and a modest budget to plan their lessons is a direct investment in a better future. It will also help retain teachers in the job. On the other hand, allowing lesson planning to remain shadow work ensures progress is not made. A lack of progress means students will not receive the most relevant, targeted work. This has flow on effects for student engagement, student outcomes, and teacher retention. These are all metrics that need to improve. Bringing teachers’ shadow work into the light by acknowledging, timetabling and budgeting for lesson planning is the first step to revitalising a profession I look forward to returning to.